Visiting the great hunters of the woods

Carcass“. A word that usually does not belong to the vocabulary of my winter walks. Well, today it is not about a usual winter walk. But about a small, fine and genuine expedition tour.

In the shady valley, we were standing knee-deep in the snow. Ahead of us the last remnants of an otherwise fairly fresh appearing roe deer carcass. Only the head, the slightly twisted spine and the two hind legs are left. Clear paw prints of several lynxes surround the carcass. In the previous evening they must have enjoyed a veritable feast here. They didn’t get it from the grocery store. But of course hunted it themselves.

In the Carpathian Mountains

This is the L’ubochňa Valley in Slovakia. Located in the Velka Fatra National Park (Greater Fatra National Park), the surrounding mountains are up to almost 1.600 meters high. They form something like the last significant alpine elevations of the huge Carpathian arc. Before it finally flattens out towards the west and in the plain.

The L’ubochňa Valley is 25 kilometers long. It is the longest valley in Slovakia. It also represents the major part of the overall good 400 square kilometers of the Greater Fatra.

One of the typical signs for national parks indicates the entrance to the local protected area. Built of long, sturdy wooden planks, it looked so inconspicuous that I noticed it only at the third time we drove through.

Eight o’clock. Each morning we drove at the same time into the valley. It was the beginning of February, the valley is covered by a deep layer of snow. We were looking for traces of the great hunters of the woods. „We“ were twelve amateur researchers and we share a common interest in the „Big Three“ – wolf, lynx and bear, which are native to the Carpathians. That’s why we support a team of local researchers.

In groups of four, we would roam the national park for several hours each day together with the researchers and expedition leaders. We help to gather evidence of the presence of predators and prey. So as to be able to collect reliable data on the wolf, lynx and bear population.

Slovakia is one of the European countries, where the majority of these animals lives in their natural habitat. However, the official figures are much higher than the estimation of local researchers: some assume that a population of 2.000 wolves exist in the country, others estimate a maximum of 400. Some speak of 2.400 bears in Slovakia, the others say, there’s not more than 800 of them. The differences in the estimation for the lynx is similar. The lynx – Europe’s biggest feline predator – is considered as endangered across the continent. This is reason enough to check at the populations in the valley. Especially in winter, they can live quite undisturbed in their environment.

Tourism and timber industry

The National Park Authority estimates that around 500.000 tourists visit the Greater Fatra annually. But only a fraction is likely to be out and about in the L’ubochňa Valley. And particularly during the winter, only a few handful of visitors would probably find their way here, as the narrow road that runs through the valley is closed to motor traffic. A special permission is needed to enter by car. There is no exception for the expedition team, foresters and employees of the timber industry.

Every day we see large timber transports with their heavy cargo driving out of the valley. Throughout the past years the loggings has supposingly doubled. We learned that the wood is mainly sold to Poland and Scandinavia. Facts, that don’t quite fit to the principals of a national park. Usually, there should not be any commercial logging in a national park. Instead, sustainable methods to preserve the nature should be promoted.

Science light

Our amateur research group is a good cross section of travellers from different countries, ages and professions. The majority comes from the UK or German speaking regions. The others originate from Belgium, Australia and from the Ukraine. You’d find the high school student, the fund manager, a zoo keeper or the marketing expert in our group.

We are all travellers who prefer snow stomping instead of sun bathing, looking to do something meaningful during the holidays. There are offers available in great numbers for folks like us. Popular in the English-speaking region is the so-called volunteer travel or voluntourism, and it is widespread since many years.

Our participation in the Slovak predator research project is just one form of this voluntourism. At the same time it is a very special type, because the idea behind projects like these is to get professional scientists together with interested amateurs.

Together, we contribute to the field research of the Greater Fatra. Gathering information. At the end of the week we walked a total of 228 kilometers on 17 different routes. We found 10 lynx tracks and 23 wolf tracks. Only the bears can not be tracked. – That’s no surprise since they hibernate in their caves.

After our week’s expedition, the results of the field research will be summarized, professionally analyzed and interpreted. Both participants and the public will be given a detailed expedition report. The credibility of the project and the usefulness of the work are simply a must for anybody involved in the project. Thus, a non-profit conservation organization must legitimize its offers as much as any other commercial operator of volunteering trips.

Researchers’ trick: „Breaking the highways“

Out in the forrest, we spend little thoughts on those topics. Instead, we walk behind each other in our snowshoes. In this way, we created little „highways“ through the snow. Thats how the researchers call it.

In nature, its all about life and death. About wasting or conserving energy reserves. And so wolves and lynxes prefer moving on the highway too, or rather, tracks that are already there instead of creating a new trail each time through the snow covered landscape. This conserves energy, and is important for survival.

With a little luck, we found some fresh animal tracks while walking in one of our „highways“ a few days later. And with more luck we found pictures of animals, big or small: Along such a path, we installed new photo-traps or swapped memory cards from cameras that were already put up. And we hoped that wildlife and predator would soon pass by.

Yet, not much happened. During the first days, we found traces of pine martens, foxes and of roe deer. And red deers, red deers, red deers. We had to be contented with the small highlight, which was a golden eagle that rose from the ground with the force of its powerful wings imprinted in the snow.

On the wrong track

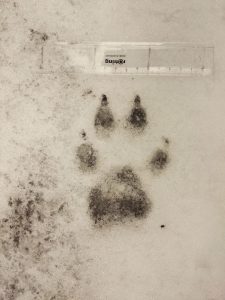

Being misled by a wrong track belongs to part of the (amateur) researchers work too. And it happened: In one of the many tours, we were so happy to have discovered a wolf track. In the ~70 cm wide snow shoe track from the previous day, we saw a paw print. We went through all the steps we learned: Marked the references in our GPS device that reliably recorded our route since the start of the morning. Whipped out a ruler and measured the size of the print. We jotted down the width and length. 8.5 by 11 centimeters. And then we wrote down the data with a pencil on a data sheet. We made a photographic evidence. For just about five minutes, we enjoyed our success. It ended when the expert told us that he was doubtful. Some evidence indicated that it was not the footsteps of Isegrim. A few more minutes later it was certain: No, those were only the traces of a big dog that accompanied a ski tourer!

Lynx tracks!

More promising were the news that reached us via walkie-talkie from the valley. Two groups were successfull that afternoon: Both groups found a fresh carcass. Surrounded by countless lynx or wolf tracks respectively. This made it clear for us how the work would start the next day: Starting from the carcass, the tracks will be followed. Anything that the lynxes and wolves have left, will be collected: Urine enters little test tubes, scat is put in small plastic bags. Later everything is evaluated by the professionals. In case of doubt, one can not conclude that it would be the presumed species. In the best cases, you can precisely describe which animal crossed our paths.

Muro, a lynx male is such a special case: A few years ago he was released to wilderness together with his sister Lisa. Both siblings were born in the zoo in Ostrava. As babies they have been reared by the gamekeeper Milos Majda. They were first brought up in an apartment in Bratislava, and later in a basic mountain cabin in the L’ubochňa valley in the Carpathians. In both places, the lynxes destroyed gradually everything they found. Furnitures, tables, beds. They soon got an outdoor enclosure and explored the surrounding forrest on extensive tours. Until one day when they eventually did not return. Tomas Hulik documented this lynx reintroduction project with his camera, from which the film „The lynx liaison“ originates.

When the lynx siblings disappeared in the mountains, the researchers wondered whether it was too early for releasing the lynxes. Would they survive on their own? With the help of a large live trap the researchers tried to re-capture the lynx, assembled from long wooden boards. But the lynxed never showed up again.

We stood one afternoon in the middle of a densely wooded hillside exactly in front of this wooden crate . Further up we discovered lynx tracks. Very possible that these are traces of Muro, says Tomas. After all, it used to be the territory of the young lynxes’. The chances looked good since only eight individuals are confirmed to exisit in the valley. The researchers estimated that up to a maximum of twelve lynxes could live here. And who knows: perhaps the roe deer carcass, in front of which we stood later, further down the valley, goes partly on Muros account …

I visited the Veľká Fatra National Park following an invitation of Biosphere Expeditions.